Indigenous Climate Architecture: Building with Storms Instead of Against Them

How Desert Communities Create Climate Architecture That Works with Natural Cycles

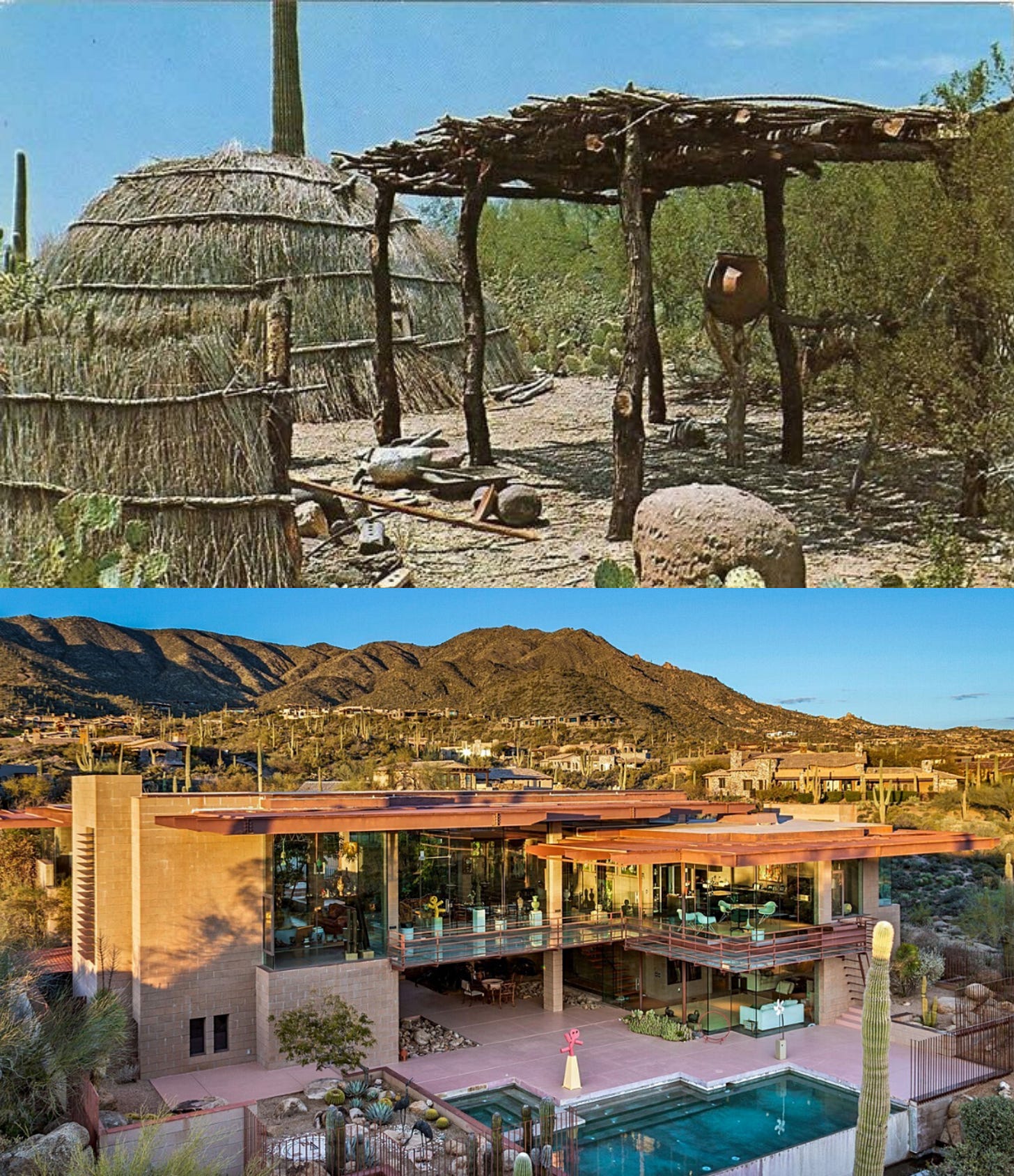

Every monsoon season here in the southern Sonoran Desert reminds me why timing matters in building for survival. Last July, watching walls of rain sweep across the valley while sitting in my climate-controlled home, I found myself thinking about the Tohono O'odham people who lived on this same land for thousands of years without central air conditioning. They didn't fight the monsoons or try to block them out. Instead, they created architectural relationships with water that turned the desert's most challenging season into their most abundant.

This intimate dance between human shelter and natural cycles embodies the kind of climate adaptation we desperately need now. As we move deeper into late summer's transitional energy, I find myself drawn to how traditional builders approached extreme weather not as an enemy to defeat but as a partner to understand. Their architectural wisdom offers something our contemporary climate crisis desperately needs: the careful integration of ancient knowledge with modern survival requirements.

The Inventory of Ancient Wisdom

The transition toward autumn asks us to take stock of what we've learned and prepare for the challenges ahead. This timing feels particularly relevant to climate adaptation, where communities must assess both environmental threats and traditional knowledge before designing resilient infrastructure.

The detailed observation and knowledge transmission that sustained desert communities for millennia offers models for contemporary climate response. Before the Bureau of Indian Affairs began drilling permanent wells in the 1920s, the Tohono O'odham practiced what they called "ak cin" farming, monitoring weather patterns for storm cloud formations and quickly preparing plantations for seeding as monsoon rains flooded their lands. This wasn't random opportunism but sophisticated meteorological observation passed down through generations.

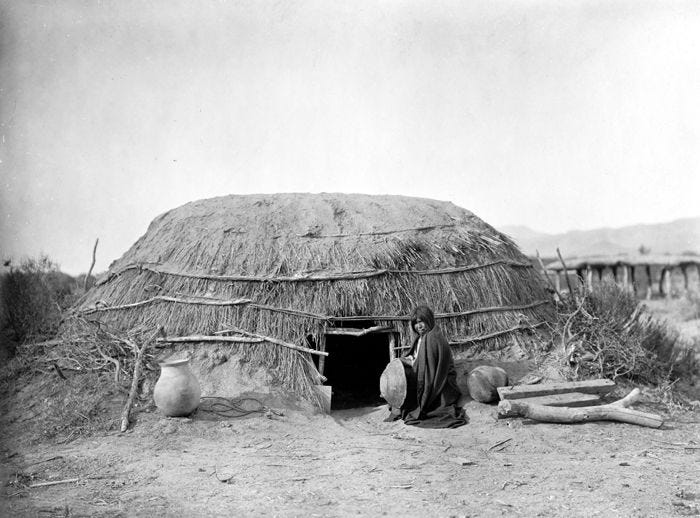

Their summer structures, called "wattos," were open-air shade ramadas with dirt floors that they would wet occasionally during the hottest parts of the day. At night, they opened their homes completely to cooling breezes that lasted through the evening. These weren't primitive shelters but precisely engineered responses to extreme heat that modern architects are now studying as we face unprecedented temperature increases.

What strikes me about these traditional approaches is how they emerged from patient observation rather than technological dominance. Communities developed building practices through generations of watching weather patterns, testing materials, and refining techniques that could adapt to changing conditions.

Contemporary Climate Justice Architecture

Today's most innovative climate adaptation projects echo these thoughtful approaches to environmental challenges. In Assam, India, where flooding has become an annual disaster affecting nearly a million hectares yearly, the Mising and Deori communities build "chang ghars," bamboo houses on raised stilts that allow flood waters to flow beneath while keeping families safe above. These structures use locally sourced bamboo and traditional building techniques that modern architects are now adapting for contemporary climate resilience projects.

The Assam State Disaster Management Authority has begun incorporating these indigenous methods into official flood management strategies, recognizing that traditional knowledge holders developed sophisticated responses to extreme weather over centuries of observation and adaptation.

In Nepal, Practical Action works with communities to repair canal systems and build bio-dykes using indigenous techniques that provide water access while reducing flood damage. Their 220-meter bio-dyke on the Karnali River protects 135 households from flooding while using entirely natural, locally available materials that the community can maintain themselves.

These projects demonstrate how contemporary climate adaptation benefits from what indigenous communities have always known: lasting resilience comes from working with natural systems rather than against them, using materials that communities can access and maintain, and building knowledge systems that can adapt to changing conditions over time.

Monsoon Architecture and Desert Wisdom

Living through the intensity of Sonoran monsoons has taught me something essential about climate adaptation: you cannot separate water management from community survival. The Tohono O'odham developed sophisticated flood farming techniques that captured monsoon runoff in carefully designed basins and channels, turning destructive flash floods into agricultural abundance. Their traditional homes were positioned to take advantage of natural cooling patterns while their agricultural systems worked with rather than against seasonal flooding.

My own experience with summer storms here reveals the precision required for this kind of environmental partnership. The difference between a monsoon that destroys and one that nourishes often comes down to infrastructure designed with intimate knowledge of local water patterns, soil types, and seasonal rhythms that can take generations to understand fully.

Contemporary architects working on climate adaptation are rediscovering these principles through projects that integrate traditional water management with modern building techniques. Community centers designed to serve as cooling shelters during heat waves incorporate passive airflow systems learned from traditional desert architecture. Flood-resistant housing projects use elevated foundation techniques refined by communities that have lived with seasonal flooding for generations.

The precision required for this kind of design work reflects the detailed observation that traditional builders mastered through centuries of refinement. These buildings must function during normal weather while providing protection during extreme events, requiring careful planning that balances multiple environmental factors.

Traditional Knowledge as Climate Technology

What strikes me most about traditional climate adaptation is how it integrates infrastructure with community knowledge systems. The Australian Water Association documents how Aboriginal communities in New South Wales maintained oral records of flood and drought cycles stretching back thousands of years, offering climate data that far exceeds Western meteorological records. David Kirby, a Ngemba man and water management expert, notes that Indigenous communities operated with a "reverse triple bottom line" where environmental health came first, supporting social and economic wellbeing rather than the other way around.

This careful prioritization of environmental relationships created architectural traditions that modern climate adaptation is now scrambling to recreate. In Sri Lanka, the ancient tank cascade system managed water and flood control through carefully designed stone structures that captured monsoon runoff while preventing erosion and supporting agricultural cycles. These systems functioned for over a millennium before colonial interventions disrupted their maintenance.

Contemporary climate justice movements are working to revive these approaches through community-controlled adaptation projects that center frontline knowledge in planning processes. Rather than imposing external solutions, these projects begin with careful documentation of traditional practices and environmental observations before integrating modern materials and construction techniques.

The wisdom embedded in these traditional systems challenges contemporary assumptions about technological progress. Communities that survived and thrived in extreme environments developed building practices that were simultaneously more sophisticated and more sustainable than many modern approaches to climate control.

Building for Transformation

As we move through late summer toward autumn's dormant months, traditional building practices offer guidance about preparing infrastructure for uncertain futures. The thoughtful approach that sustained desert communities through extreme weather cycles provides a template for contemporary climate adaptation that prioritizes community control, environmental relationships, and adaptive capacity over rigid technological solutions.

These traditional approaches suggest that climate resilience requires more than individual buildings designed to withstand specific threats. Instead, lasting adaptation emerges from architectural systems that strengthen community bonds, preserve cultural knowledge, and maintain relationships with natural cycles that support long-term survival.

The late summer energy of assessment and preparation feels particularly relevant as communities worldwide face unprecedented climate challenges. Like the Tohono O'odham farmers who monitored cloud formations and prepared their fields for monsoon floods, contemporary climate adaptation requires precise observation, community knowledge, and infrastructure designed to work with rather than against environmental changes.

The Future of Climate Territories

The convergence of traditional knowledge with contemporary climate science offers hope for adaptation strategies that serve frontline communities while preserving cultural wisdom. Projects that center indigenous expertise create infrastructure solutions that are environmentally appropriate, economically sustainable, and culturally meaningful for the communities that maintain them.

This integration demonstrates that resilience comes not from fighting environmental changes but from understanding them deeply enough to build with them skillfully. The architectural wisdom of communities that survived and thrived in extreme environments offers more than technical solutions. It provides a different relationship to place and time that prioritizes long-term survival over short-term convenience, community knowledge over expert authority, and environmental partnership over technological domination.

In our current moment of climate crisis, these ancient approaches to building with natural cycles rather than against them offer pathways toward infrastructure that can adapt, survive, and even flourish as environmental conditions continue to change. The precision and patience required for this kind of adaptation reflects something essential about sustainable design: it emerges from intimate relationships with place that can only develop through careful observation over time.

Resources for Deeper Research

Tohono O'odham Nation Water Resources - Official tribal climate adaptation planning and traditional water management documentation

Practical Action: Indigenous Water Management - Global documentation of traditional climate adaptation techniques

Australian Water Association: Indigenous Flood Management - Aboriginal water management knowledge and climate data

Traditional Building Techniques for Flood Adaptation - Community-based climate resilience in South Asia

Institute for Tribal Environmental Professionals - Tohono O'odham climate change adaptation planning and traditional knowledge integration